Upcoming Program Takes a “Peek at Prohibition”

By Traci Langworthy

Marion Manning made a grisly discovery along the lakeshore near Sheridan Bay Park in April of 1928. There before him in the thawing lake ice was the body of a man, frozen in a state of decomposition.

If the initial find weren’t jarring enough, the ensuing investigation brought more startling news. When the deceased was identified as a New York City man wanted on federal bootlegging charges, locals might have disbelieved their ears. Then again, they were living in atypical times. What might have been a big headline in another era was a Page Eight follow-up report at the height of Prohibition.

As it turned out, the dead man was one of two suspects attached to a rum-running vessel that wrecked near Dunkirk the preceding January. Though his story ended more dramatically than most, it was highly representative of the time and place. After the 18th Amendment banned the sale, manufacture, and transport of alcoholic beverages beginning in 1920, illicit activities involving liquor became commonplace around the nation. But our area witnessed more than its fair share.

The evidence abounds in area newspapers – as Karen Livsey and Sam Genco quickly found out when they began researching the topic about two years ago. In addition to colorful press coverage, they also found a treasure trove of information in the files of Livsey’s relative, Axel Levin of Busti. Elected Chautauqua County Sheriff in 1924, Levin was on the front lines of law enforcement’s efforts to crack down on violations.

Those curious to learn what Levin’s records reveal can mark their calendars for Tuesday, June 10, when Genco and Livsey will present “A Peek at Prohibition in Chautauqua County” at the Sheridan Historical Center. The 7 p.m. program is free and open to the public.

One thing the speakers will surely confirm is the difficulty of Levin’s job. After the 18th Amendment became the law of the land, Congress established a system of enforcement under the Volstead Act. U.S. Marshals in the Bureau of Prohibition were the principal enforcement agents, but they relied extensively on local law enforcement.

“It wasn’t a simple matter of raiding saloons and stills. Sellers and consumers of alcohol were inventive in their efforts to circumvent the law,” Genco and Livsey noted. Country “dance halls” might pop up on one farm, be shut down, and surface again at another man’s barn. During one week in August of 1925, the sheriff’s men, along with state troopers, raided five separate public barn dances. Speakeasies flourished, meanwhile, in the county’s villages and cities.

But the hardest task of local law enforcement may have been curbing the importation of alcohol along the Lake Erie shoreline. On April 21, 1927, The Silver Creek News carried a long indictment of Prohibition’s many failures by George Ramsay McIntyre, financial editor of the Chicago American. A native of Silver Creek, McIntyre stressed the “trail of illegal traffic in liquor” that could be followed in “thousands of smaller places throughout the land” in addition to the largest cities. Feeding this trail was an appetite for greed that knew no moral mounds, let alone international borders. “Thousands of miles of border between this country and Canada must be guarded against smuggled liquor,” he stressed. “The United States has already spent many millions in the effort to prevent the landing of liquor on our shores, but it has gone forward steadily and uninterruptedly.”

As Genco and Livsey further detailed, “the Volstead Act defined intoxicating liquor as any liquid with over one-half of 1 percent alcohol, although Canada’s limit was 2.5 percent. Canada’s ‘dry’ period also started and ended earlier than in the U.S. and the exportation of liquor from Canada was never illegal.” These conditions were ripe for exploitation. With the lucrative rum-running trade that developed across Lake Erie, it was not uncommon for “running gun battles” to erupt at the lakeshore as federal agents “pursued, and occasionally caught, the rum-running vessels,” Genco added.

Such wild scenes make a dead body in the ice seem tame by comparison. They also provide helpful context for why an accused liquor trafficker might have met his tragic fate along the shore of Chautauqua County.

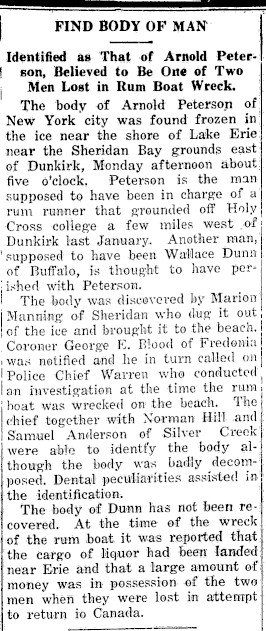

The Westfield Republican article reporting on Manning’s grisly find identified the body as that of Arnold Peterson of New York City. Authorities believed Peterson and his partner, Wallace Dunn of Buffalo, were on their way back to Canada at the time their boat floundered, having already unloaded their cargo in Erie, Pa. Dunn was assumed to have perished in the lake, as well, though his body had not been found.

Did the two men abandon ship before the boat scuttled on the beach? Or did they leave the wreck to avoid being apprehended, only to succumb to stormy surf? Either way, it seems Lake Erie became the decider of their fates.