Honoring the Legacy of Haven & Kenyon Pottery

By Traci Langworthy

It’s been nearly 200 years since the kiln of Elias Haven and Joseph Kenyon ceased operating along the bank of Scott Creek. But their legacy lives on through the work of two local men – one of whom has given new life to the same vein of clay the old potters tapped.

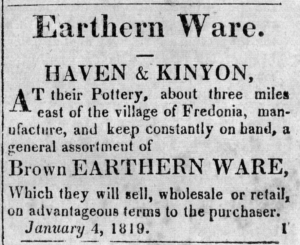

Located on what is now U.S. Route 20 near the intersection with New Road, the Haven and Kenyon pottery shop was in operation as early as 1818. That makes it the second oldest pottery manufactory in Chautauqua County, according to local historian Vincent Martonis. But its significance goes beyond local history. “Haven and Kenyon is easily one of the most important pottery sites in New York State,” Martonis shared.

Martonis has been working to raise awareness of the site since the 1980s. In 1986, after four years of research, he was able to confirm the approximate location along Scott Creek in Holland Land Company Lot 60. Fast forward to 2024. In March, Martonis published The Haven and Kenyon Redware Pottery of Sheridan, N.Y., a richly illustrated book that’s been decades in the making. Not long after, he also shared his findings at the prestigious Bennington Museum in Vermont.

Back at home, Martonis’s research was the subject of a historical society program in late June. Those on hand were able to view a sampling of sherds, as well as the four full pieces Martonis has been able to attribute to Haven and Kenyon. The full pieces include a flask, two jugs, and a sander (used for blotting ink when writing with a quill pen). Each possesses traits of the Sheridan potters’ distinctive craftsmanship. A separate plate forms the base of Haven and Kenyon jugs, for example.

But it’s the Sheridan duo’s creativity that makes their work truly shine. The variation of colors they achieved in their glazes is “absolutely astounding,” Martonis said. With the possible exception of an early manufactory south of Rochester, “I don’t know of another pottery in New York State that can match it,” he added.

The Sheridan potters also stand out for their use of “slip decoration” on the outside of their vessels. The decorations could be as simple as lines or wave patterns drawn with the finger. But Haven and Kenyon also experimented with more complex designs, including those incised with a special tool. “Incised animal decoration is not found at any other redware site in our state before 1829,” Martonis detailed, adding, “These decorations are what make Haven and Kenyon a remarkable pottery.” One of Martonis’s favorite artifacts is a sherd revealing part of a bird decoration.

Clearly, this sort of craftsmanship deserves to be honored today. And not just with a book. This is where another local admirer of Haven and Kenyon’s work enters the story.

Earlier this year, Martonis recruited local potter Ron Nasca to fashion a Haven and Kenyon style flask using clay from the site of the pottery. Nasca also had another idea: to make Haven and Kenyon bowls for the popular “Empty Bowls” fundraiser he spearheads every fall.

Begun in Michigan in the early 1990’s, Empty Bowls is now an international fundraising model used to combat food insecurity in local communities. Potters and ceramics studios from around the U.S. donate bowls to either sell or be given away at ticketed meals.

Nasca has been a part of the Chautauqua County Empty Bowls Project for 15 years now. The first effort raised about $5,000. Since then, the program has grown to include benefit sales in both Fredonia and Jamestown garnering about $381,000 total since its inception. The proceeds go entirely to local food banks. “To use the phrase empty bowls all the money has to stay in the area that it was raised in to help feed the hungry,” Nasca explained.

This year’s fundraisers will be held on Saturday, Nov. 23 at the Wheelock Elementary School gymnasium in Fredonia and Saturday, Dec. 7 at St. Luke’s Episcopal Church in Jamestown. The Fredonia sale will feature 75 bowls crafted exclusively by Nasca from clay harvested at the Haven and Kenyon site. “They’ll have an orange paper banner on them saying ‘Haven and Kenyon clay’ from Sheridan, N.Y.,” Nasca shared.

In addition to raising money for an essential cause, the bowls will also raise awareness of our area’s rich history. As Lori Mayr, SHS president, has noted in her research, “Pottery makers provided early American settlers with much needed household goods. Handmade redware was used for storing, preparing, and serving food. Potters also formed redware into such necessities as inkwells and chamber pots.”

“Redware as a term wasn’t used until the late 1800s,” Martonis added. “At the time, it was called earthenware.” The label perfectly represents the source of materials: local clays that early potters found by walking local creeks.

Finding the clay deposits at the Haven and Kenyon site presented a bit of a challenge at first. Mayr and her husband, Stefan, also happen to be the owners of the property today. Together with Nasca and Martonis they identified a couple of possible locations. Then they went to work with their shovels. After striking out on their first attempt they hit a “really good seam of clay” about 18 inches deep at a second spot. Nasca left with two heavy buckets of promising muck.

And that was just the beginning of the process. As Nasca’s narration made apparent, it’s not just the source of the clay that makes his Haven and Kenyon bowls special. There’s a lot of time and care that goes into processing the raw material and making it suitable for the final products. Although Nasca can’t say for sure, the work is probably not unlike the work that Haven and Kenyon did to bring their visions to fruition. “The clay has a lot of rocks and twigs and whatever in it because it’s from sedimentary deposits,” he explained. The cleaning process requires several iterations and many hours of labor. “I don’t know exactly how they did it, but cleaning is essential. Throwing a pot with a big rock in it is not a fun time,” he joked.

It was also tricky for Nasca to figure out the best composition to be able to fire the clay at a high enough temperature. “They only got to about 1900 degrees,” he explained. But their final product wasn’t food-safe by today’s standards. “What we do is I fire it to 1800 degrees. Then I put glaze on it and fire it again to 2200 degrees.” The intensity of this firing process required that Nasca combine the Sheridan clay with some additional base. “The pots at Wheelock will be about 70 percent Haven and Kenyon clay and then about 30 percent other clay I added to it to bring it up to temperature,” he detailed.

Of the cleaning process, especially, Nasca joked, “It’s not a thing you’d want to do every day.” But it’s not without reward either. “It’s a labor of love for me,” he stressed. Haven and Kenyon might just agree if they were here today – although they might be surprised by the following Nasca’s work gets in 2024.

“We had 508 people show up at Empty Bowls last year in Fredonia,” Nasca noted. Those wanting to purchase one of the Haven and Kenyon bowls are encouraged to arrive early. The sale runs from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. at the Wheelock Elementary School gymnasium.

Those interested in purchasing Martonis’s book may find copies for sale at both the Barker Museum in Fredonia and Fenton History Center in Jamestown. Or, they are welcome to contact Martonis directly at (716) 208-1013. Martonis also donated a copy to the SHS for use by future researchers.